Python Multiple Inheritance

01 May 2020 · 4 min read

Inheritance, a simple and evil mechanism for re-using code, can get tricky. Traditionally, you may have encountered inheritance when you wanted to extend or override a class’s behavior.

class Pet:

def walk(self):

print("walk")

def eat(self):

print("talk")

def talk(self):

print("!@#$")

class Dog(Pet):

def talk(self):

print("Ham!")

class Cat(Pet):

def talk(self):

print("Miau!")

Fairly easy to understand and follow. Dog and Cat share most of Pet’s behavior, with some “small” particularities. Let’s say that we want to isolate particular behavior, for better testing purposes.

class Eats:

def eat(self):

print("eat")

class Walks:

def walk(self):

print("walk")

class Talks:

def talk(self):

print("talk")

def Dog(Eats, Walks, Talks):

def talk(self):

print("Ham!")

class Cat(Eats, Walks, Talks):

def talk(self):

print("Miau!")

It may look a little bit weird, but isolating eating, walking and talking, improve re-usability, and may ease testing, but adds complexity and it increases readability efforts.

What’s Dog’s or Cat’s behavior? Well, you need to look at its parents. They inherit from Eats, Walks, and Talks. That class is commonly known as Mixins. Using multiple inheritances, you can compose specific behaviors. Think about playing with Lego. Using well defined, independent components, you can build complex constructs. In practice, you may use mixins within models, forms, serializers, views, etc.

Multiple-inheritance seems to work for independent components that don’t share state or behavior. What’s going to happen when you try to combine a Dog and a Cat into a SuperPet?

class SuperPet(Cat, Dog):

pass

super_pet = SuperPet()

assert super_pet.talk() == "Miau!"

SuperPet will inherit all the methods and properties of Dog and Cat and will respect the Method Resolution Order. More exactly, the C3 Method Resolution Order, which was initially released in a paper in 1996, designed for Dylan, called “A Monotonic Superclass Linearization for Dylan”. It’s implemented in other languages as well, Raku, Parrot, Solidarity, and Perl 5 (as a non-default option).

Ok, it starts to look complicated, but basically, it just takes the methods of the left-most class, right? Almost.

class GrandParent:

def describe(self):

print("Grandparent")

class Mother(GrandParent):

def describe(self):

print("Mother, son of")

super().describe()

class Father(GrandParent):

def describe(self):

print("Father, son of")

super().describe()

class Child(Mother, Father):

def describe(self):

print("I'm child, son of")

super().describe()

child = Child()

child.describe()

>>>>

I'm child, son of

Mother, son of

Father, son of

Grandparent

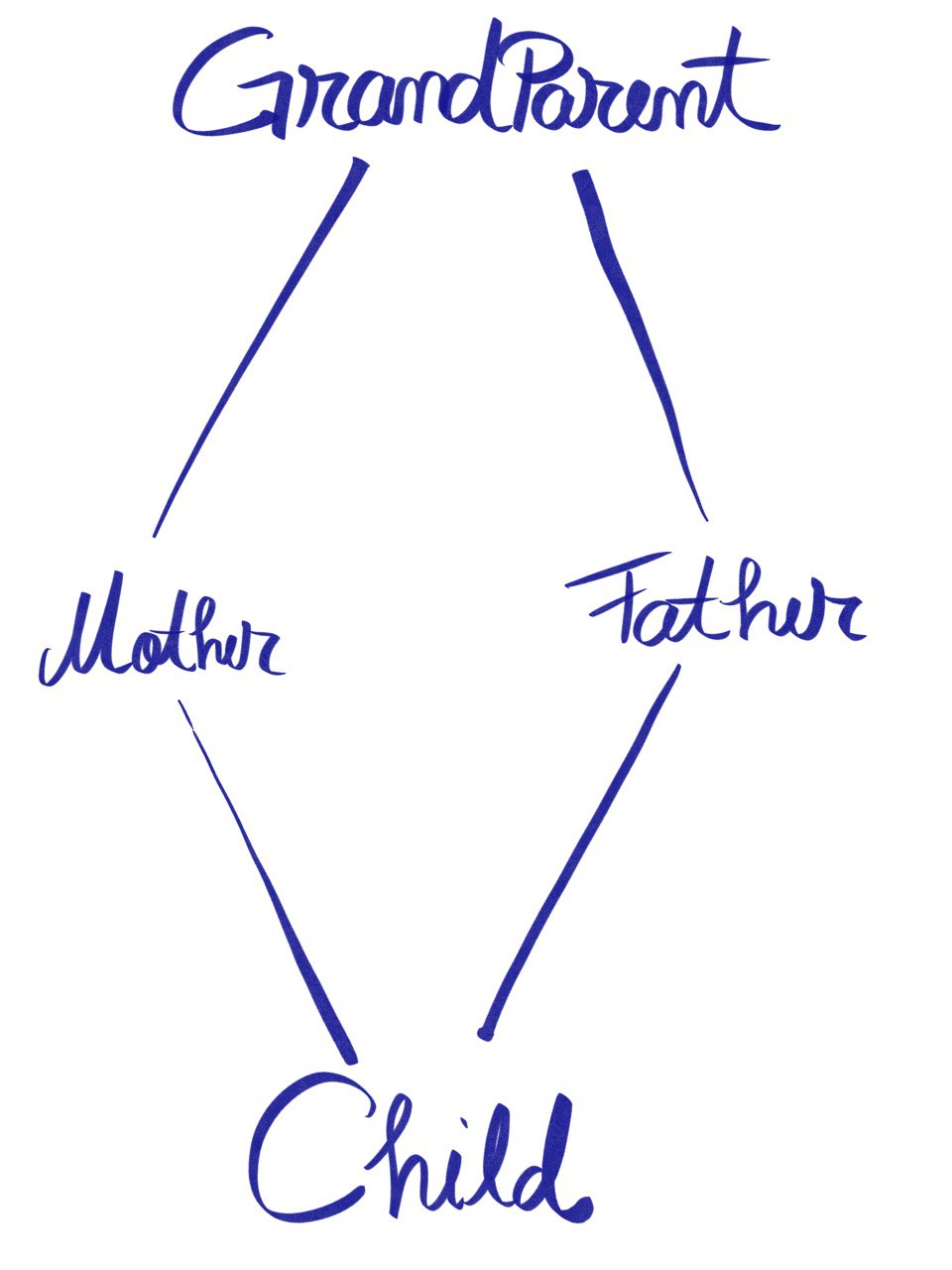

Introducing super() and we’ll discover pretty cool interactions. Going a little deeper, Method Resolution Order (further referring to MRO) represents a set of rules that compute the linearization (a scary term that represents a serial way in which nested classes inherit from each other). Basically, it flattens the graph hierarchy. From:

to something more like [Child, Mother, Father, GrandParent].

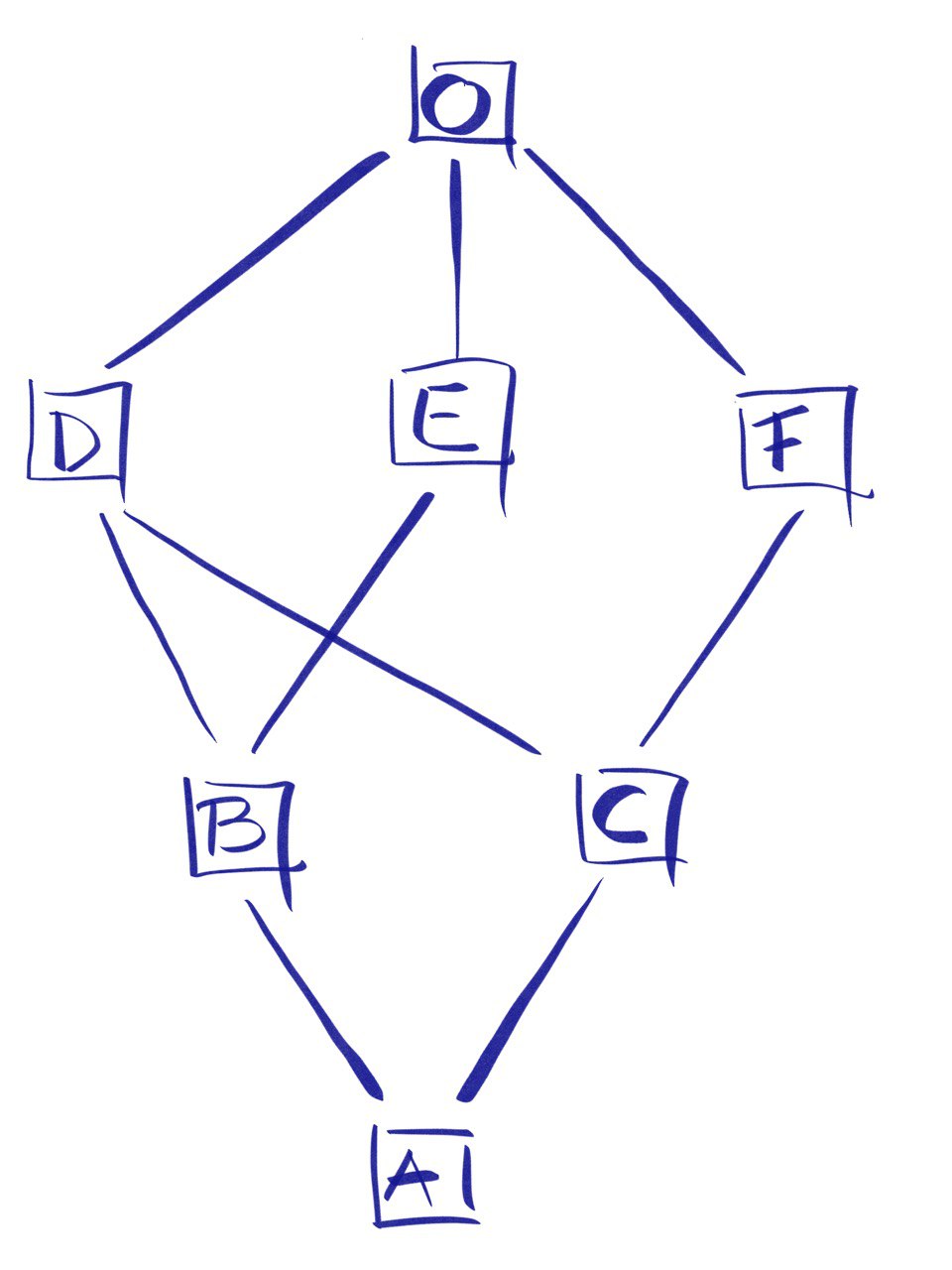

The problem above is also known as the Diamond problem. We can easily describe the linearization process as a recursive algorithm: Child + merge(linearization(Mother), linearization(Father)) or Child + the merge of linearization of the parents and the list of the parents. It seems a little trivial, but let’s try a more complex example:

class O:

pass

class F(O):

pass

class E(O):

pass

class D(O):

pass

class C(D, F):

pass

class B(D, E):

pass

class A(B, C):

pass

MRO(O) = O

MRO(F) = F, O

MRO(E) = E, O

MRO(D) = D, O

MRO(C) = C + merge(MRO(D), MRO(F) + MRO(DF))

= C + merge([D, O], [F, O], [D, F])

= C + D + merge([O], [F, O], [F])

= C + D + F + merge([O], [O])

= C + D + F + O

= C, D, F, O

MRO(B) = B + merge(MRO(D), MRO(E), MRO(DE))

= B + merge([D, O], [E, O], [D, E])

= B + D + merge([O], [E, O], [E])

= B + D + E + merge([O], [O])

= B + D + E + O

MRO(A) = A + merge([B, D, E, O], [C, D, F, O], [B, C])

= A + B + merge([D, E, O], [C, D, F, O], [C])

= A + B + C + merge([D, E, O], [D, F, O])

= A + B + C + D + merge([E, O]), [F, O])

= A + B + C + D + E + merge([O], [F, O])

= A + B + C + D + E + F + merge([O], [O])

= A + B + C + D + E + F + O

You can double check it, using the mro function:

(<class '__main__.A'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <class '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.D'>, <class '__main__.E'>, <class

'__main__.F'>, <class '__main__.O'>, <class 'object'>)

And, of course, you can have your own MRO, no problem. All you need to do is to define a method called mro inside a metaclass.

Random MRO is not that smart, but for sure is interesting.

import random

class GrandParent:

def describe(self):

print("Grandparent")

class Mother(GrandParent):

def describe(self):

print("Mother, son of")

super().describe()

class Father(GrandParent):

def describe(self):

print("Father, son of")

super().describe()

class RandomMRO(type):

def mro(cls):

parents = [Father, Mother, GrandParent]

random.shuffle(parents)

return [cls] + parents + [object]

class Child(metaclass=RandomMRO):

def describe(self):

print("I'm child, son of")

super().describe()

child = Child()

child.describe()

>>>

[<class '__main__.Mother'>, <class '__main__.GrandParent'>, <class '__main__.Father'>]

I'm child, son of

Mother, son of

Grandparent

>>>

[<class '__main__.Father'>, <class '__main__.GrandParent'>, <class '__main__.Mother'>]

I'm child, son of

Father, son of

Grandparent

Multiple inheritance can get messy and for the full story please take a look at https://www.python.org/download/releases/2.3/mro/. It can be really fun to play with, but in the long run it can be a real trouble maker.

Cheers 🍺!

Thanks @catileptic for the awesome illustrations!